Use case intended for: Spatial analist

| Before you start: | Use case Location: | Uses GIS data: | Authors: |

|---|---|---|---|

| Read Methodology Book Chapter 7 on Spatial Planning and hazard requirements | Case study of site selection for relocation in Kigali Rwanda | No | Richard SliuzasContributor: Alice Nikuze |

Introduction:

This use case sets out a procedure that could be adopted to evaluate the options for relocating settlements that have a high risk of being affected by a disaster. Much of the procedure discussed here could also be applied in a post-disaster situation, for the identification and evaluation of long term relocation options for persons initially provided with short-term emergency shelter.

Resettlement is a highly sensitive subject. Even when households are confronted with obvious risks in their present locations, involuntary displacement may be resisted as highly hazardous sites usually also offer some benefits for those who occupy them, they may for example trade off risk against accessibility to livelihood opportunities or access to services. Moreover, poorly designed and managed displacement is often known to be associated with social disarticulation and increased deprivation. Careful project planning that is sensitive to the needs of the displaced households, businesses and other activities is therefore essential. A purely technocratic approach is almost certain to face substantial resistance and may even fail entirely. It is also essential that the site for resettlement is suitable from an urban development perspective and hazard free.

Objectives:

- Identify and describe the steps in a settlement relocation evaluation

- Establish a multi-stakeholder project management structure

- Establish the scale and scope of the resettlement project

- Identify and evaluate candidate sites for relocating the settlement

- Develop plan for relocation

- Implement and monitor the resettlement process

- Provide an insight on how hazard/risk information may inform the resettlement process

- Be aware of possible dilemmas and complexities associated with relocation processes

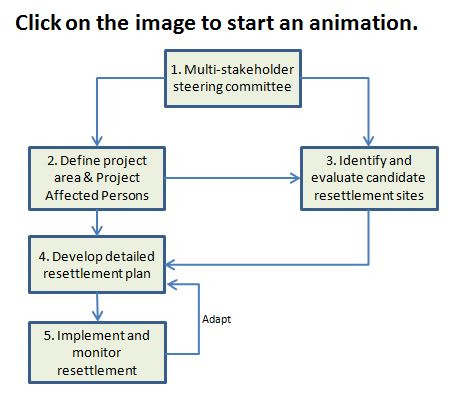

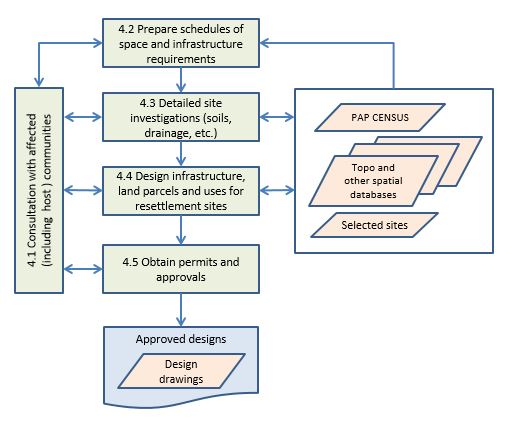

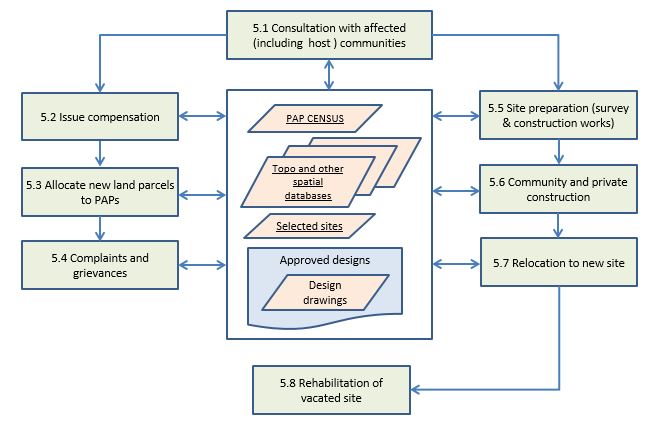

Flowchart:

Use case study area description:

Resettlement projects are complex operations. We have distinguished 5 main activities as shown in the flowchart. Each step is described in more detail below and more complex flowcharts are also available for each of these main steps, combined with more detailed descriptions of each sub-activity and critical issues and concerns that need to be considered if they arise during each stage of the process. Emphasis is placed on the use of hazard information in the process but other issues will also require attention for successful resettlement to be achieved.

Problems definition and specifications:

A resettlement project consists of both hard (technical) and soft (institutional) elements. Finding and maintaining a good balance between these two elements is important. Typical problems and questions to address in such a project are:

- Who to involve in the technical steering committee?

- How to engage persons affected by the project (PAPs) in an effective and productive manner throughout the entire project period?

- Is there any scope for reducing the need to relocate a community through the adoption of special mitigation measures?

- What is the extent of the relocation area, the number of affected people and the amount and value of affected assets?

- Are there sufficient hazard free resettlement sites for relocating all PAPs and their assets in such a manner that their livelihoods can be improved or at least maintained at pre-project level?

- Is the relocation acceptable to all PAPs and the host communities?

- Is the compensation system fair, adequate and transparent?

- What design guidelines and regulations need to be considered in the planning and design of the new settlement?

- Are any special measures required (e.g. extending the public transportation network, creating new community facilities and services, etc.) required to make the resettlement site more sustainable and liveable?

Data requirements:

- Risk assessment for current situation: data are required for all relevant hazards (e.g. flood, landslide, earthquake, storm surge, etc.) for a given context. Details of typical data needs can be found in the Data Management Book chapter 4.1. Data should be preferably be based upon local hazard assessments suitable for detailed risk assessment and decision making. If detailed local data are unavailable, planners could refer to national level data for indicative assessments and supplement these with professional guidance from hazard professionals. Risk assessments should be carried out using a multi-hazard approach see Methodology Book Chapter 5.1.

- Inventory of PAPs, real estate and assets to be compensated or relocated. This may include compensation for crops for example or other assets related to livelihoods.

- Spatial and socio-economic data for site evaluation/selection process e.g. land register (ownership, value, use), multi-hazard risk assessment, detailed soil and drainage studies, topographic data, land use, etc.

- Guidelines and regulations for settlement planning (plot sizes, road dimensions, drainage, water supply and sanitation, electricity, telecom, community facilities etc.)

Analysis steps:

General Application

The relocation process consists of 5 main activities, each of which is briefly described below:

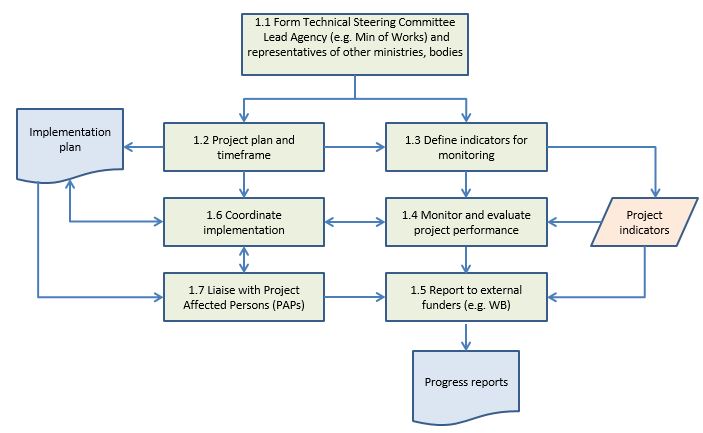

Step 1: Formation of a multi-stakeholder steering group

The relocation process consists of 5 main activities, each of which is briefly described below:

Formation of a multi-stakeholder steering group: Relocation processes inevitably involve a large number of stakeholders from public, private and civil society. In addition to creating a technical project management unit to plan, design, and implement the work it is essential to establish clear lines of communication with all involved parties, especially those who make up the target community. These groups should be fully aware of the legal frameworks and procedures that guide and facilitate the relocation process and the financial and technical resources that are available.

Sub-processes concern the following issues:

a. Formation of a technical steering committee to plan and manage the entire project. Normally this would be led by a senior staff of the Ministry of Public Works (or similar body) and include representatives of other major ministries and bodies engaged in different aspects of the project. These persons would be responsible for coordinating activities across ministries.

b. Project planning and timeframe: set out the main activities and time frame and adjust planning according to progress

c. Defining indicators for internal and external project monitoring

d. Monitoring and evaluating project performance against the established indicator framework.

e. Reporting project performance to external agencies (e.g. funding agencies such as The World Bank)

f. Coordination of the implementation process: ensure that appropriate ministries are engaged in the project and execute their duties in a timely and efficient manner according to the goals and principles of this project.

g. Liaise with project affected populations as and when required to ensure the required level of collaboration and support for the project.

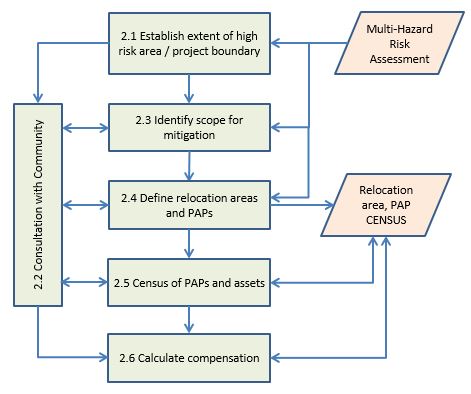

Step 2: Define project area and elements at risk

In this activity the boundary of the area for which resettlement should be executed is defined and an enumeration of all elements at risk should be carried out (elements at risk here is taken to include all physical structures and infrastructures as well as the assets within them, and all households, businesses and other activities that are found within the target area). The boundary definition will initially be driven by the area that is identified as being exposed to an unacceptable level of risk - both quantitative approaches (Quantitative Risk Assessment or Event tree analysis) and qualitative approaches (Risk Matrix or Indicator Based) can be used to identify such areas. Quantitative approaches are more data demanding and the risk matrix approach is often suited to spatial planning situations in which the relative impact of alternatives can be considered by stakeholder groups - see for example Methodology Book Chapter 5.1. Essentially though the decision of what is an unacceptable level of risk is a political one, but it is also one with important socio-economic implications for land owners and most importantly for those households or organizations that may be displaced as a result of that decision.Using a risk matrix stakeholders can compare hazard intensity or frequency with likely impact to classify levels of risk for each hazard type (for a brief explanation see Use Case 2.1 National land use planning). Distinctions may be made between activities that entail a high concentration of highly vulnerable groups (e.g. schools or nursing homes) where disaster impacts could be very high and those that are less vulnerable (e.g. warehouses for non-hazardous materials). It is common to determine 4 levels of risk: low risk - location can be used for human/economic activities; medium risk - location can only be used by land uses with little sensitivity to the hazard (e.g. warehouses with non-hazardous substances) subject to appropriate mitigation measures being taken (e.g. construction of a dike, raising the site level, building a retaining wall, building a gully to direct debri flows away from settlements, creating an early warning system and evacuation plan, etc.); high risk - location not to be used for human/economic activities. Relocation sites for human settlement should only consider locations for which the risk assessments for each hazard are in the low category. If hazard data is incomplete or not of the required level of detail, expert opinion should be sought for each site.

The target area definition should also consider the viability of any residual settlement area that may be left out of the relocation process. Should the residual area not constitute a socially and economically viable community then it too may require relocation so as to avoid structural deprivation through the reduction of its socio-economic base. Community participation is therefore a critical component of the boundary definition. The activity should produce a detailed list of requirements for potential resettlement sites and an initial feasibility study for the relocation process including estimations of compensation and financial assistance requirements for the displaced. Two methods that can be very useful in this process are Cost-Benefit Analysis (CBA) and Multi-Criteria Evaluation (MCE) (see Methodology Book Chapter 6.1 for more information). For example, CBA can be useful in comparing the costs and benefits of mitigation measures versus relocation. MCE can be used to combine various indicators of hazard and vulnerability to determine risk levels, and in comparing the suitability of various sites for the purpose of relocation, combining risk indicators with more general planning indicators related to accessibility, land ownership or land value for instance.

Sub-processes concern the following issues:

a. Establishing the project boundary on the basis of multiple hazard risk assessment data (this involves deciding on the acceptable or tolerable risk level for each hazard individually and then combining them, adjusting the boundary to parcel boundaries or topographic features where appropriate).

b. Community participation: effective community participation is a vital ingredient for project success in each process of the project. A committee that includes both technical staff and community representatives is needed to raise awareness and facilitate information exchange.

c. Identifying scope for mitigation: all options for mitigating hazards should be explored prior to considering the relocation strategy, given the latter's complexity and impact. CBA can be used to evaluate various options including relocation.

d. Define relocation areas, PAPs: determine precise boundaries of the areas and households and organizations which will be relocated.

e. Undertake a detailed Census of PAPs and their assets including their livelihood assets such as crops etc.

f. Determine the value of assets and calculate compensation for all PAPs: this should be timed in such a manner that relocation is eminent so as to avoid complaints and grievances associated with undervalued assets (e.g. crops) which have a seasonal fluctuation. Where possible use in-kind compensation (e.g. provide a new house rather than cash) to minimize the cash transactions required and avoid possible redirection of funds for non-residential purposes.

g. Prepare guidelines for future use and management of the vacated settlement site. It is important that measures are adopted to protect the vacated site from reoccupation that will regenerate the risk situation. As its location has apparently some appeal, that some people trade-off against risk, it may be quite difficult to protect it from reoccupation. Measures that could be considered include: a wide awareness raising campaign with local communities about the danger of occupying the site (this could include through media campaigns, flyers, signs, etc.); regular site inspections and monitoring coupled with rapid intervention actions to remove ‘invaders' quickly without further compensation; be prepared to provide information to invaders on suitable sites within the vicinity as alternatives; etc. (see also step 5g related to rehabilitation of the vacated site).

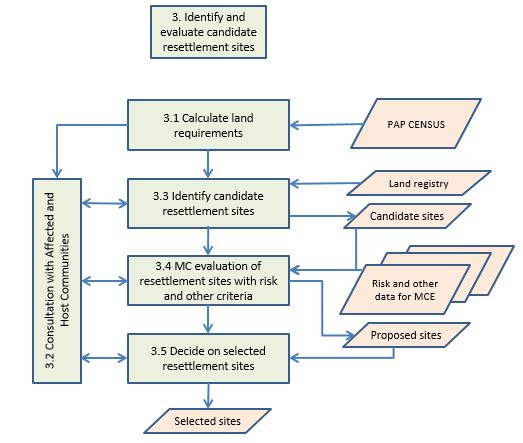

Step 3: Identify and evaluate candidate resettlement sites

The main outputs of activity 2 provide a basis for the identification of candidate resettlement sites. Ideally candidate sites should be large enough to accommodate the entire target community, be as close as possible to the original site to reduce secondary effects of relocation such as increased travel costs, loss of livelihoods, etc., affordable, easily accessible, readily serviceable and of course hazard free. Options that involve resettlement over several sites may also be feasible and should not be immediately excluded. Land tenure issues and the possible views and needs of the current owners of the potential sites need also to be considered. An inventory of each site according to the selection criteria should be made. The site evaluation and selection process should be carried out in an open and transparent manner. All key stakeholders, including the current owners of potential sites, should be heard and engaged in the comparative evaluation of the potential sites. The final selection of site(s) will likely require political ratification before detailed plans can be prepared. As long delays may arise as a result of resistance to the process both from the displaced and from the proposed locations' land owners, much attention should be given to the governance process of resettlement. In this regard, public land may be preferred above private land for resettlement where feasible.

Sub-processes concern the following issues:

a. Detailed calculations of land requirements for all public and private purposes in the new settlement (i.e. including all roads and community facilities and services)

b. Community participation (see 2b above)

c. Identify candidate resettlement sites: search land register (if existing) for lands which would satisfy the basic area requirements for resettlement. Priority should be for public lands that would not require additional capital for acquisition.

d. Evaluate all candidate sites against risks and other spatial criteria (e.g. proximity to existing roads and other infrastructure, suitability for required livelihood activities, proximity to existing site, etc.). This MCE analysis should result in a prioritized list and map of sites that satisfy the required resettlement demands. The Technical steering committee should approve the selected sites and propose them for ratification by the appropriate political bodies.

e. Decide on sites: this step is the final political approval of the resettlements sites. The target communities should be informed about the outcome without delay to maintain a high level of transparency throughout the process.

Step 4: Detailed resettlement plan

The planning of the new settlement follows a similar process as any local spatial plan (see local land use planning Use Case 2.2). One important difference though is that in this case the new owners (PAPs) are already known and should be actively engaged in design process in order to maximize support for the relocation and a sense of ownership even prior to relocation. The final design should also be approved by relevant planning authorities as with any normal development scheme.

Sub-processes concern the following issues:

a. Community participation (see 2b above)

b. Detailed schedules of land and infrastructure requirements for all public and private purposes in the new settlement (i.e. including all roads and community facilities and services). This schedule forms the basis for the final design for the new community.

c. Site investigations: prior to the final design it is important to undertake some additional investigations of soil and drainage conditions to ascertain load bearing capacity for structures and roads, fertility (if agriculture activities are expected), and drainage conditions. These aspects may require specific attention in the design or supplementary guidelines for building and infrastructure designs.

d. Design of settlement: a detailed plan for land subdivision and use, infrastructure provision that is complete, satisfies the minimum requirements for planning and building approval processes and gives due consideration to potentially hazardous situations and hazard reduction through sound and construction processes).

e. Permits and approvals should be obtained from the relevant authorities for all aspects of the design.

Step 5: Implement and monitor resettlement

This step includes the creation of the new settlement through a combination of public and private investments, the compensation and relocation of the residents and activities, the demolition of old settlement structures and re-landscaping, and monitoring and evaluation of both the former and new sites.

Sub-processes concern the following issues:

a. Community participation (see 2b above)

b. Payment of compensation according to the determine amounts (see 2.f above): payments should be made as close as possible to the time of relocation to avoid misuse of funds

c. Allocate new parcels: each affected land holder should be allocated a new parcel of comparable value and utility in the new site. Tenants will likely require different treatment but they should be provided with an option for comparable rental housing or an option to become a land/house owner.

d. The complaints and grievances process has been included as it can be anticipated that there will be instances where PAPs are dissatisfied with some aspect of the relocation process. It is therefore worthwhile to establish a small committee or at least a systematic procedure to deal with such cases. The role of the committee and the rights of PAPs to address it should be widely communicated.

e. Site preparations concerns all activities required to be carried out prior to the construction and occupation of buildings. These include land surveying and plot demarcation and main infrastructure construction (e.g. roads, water and sanitation, telecom if relevant). Once these are in place building construction can commence.

f. Construction of private homes, businesses and any public services and facilities such as schools, health services, police stations etc. that may be required. The need for the latter will be determined by the scale of the project and the availability of similar facilities in the vicinity of the resettlement site.

g. Relocation of PAPs can occur once habitable buildings have been constructed and approved by relevant authorities. The degree of public coordination required will depend on the scale of the whole project and the number of PAPs.

h. The final step concerns the rehabilitation of the vacated site. This step may involve demolition of abandoned structures, including recycling of materials where possible, and the restoration or rehabilitation of the landscape according to appropriate design principles. The precise design considerations will depend on the site characteristics and the possible future roles that the site could play (e.g. for flood water retention and or recreation, etc.) and detailed planning and designing may be required (see also step 2g above).

Example Application

Currently, there is no well documented example from one of the project countries to examine how resettlement sites could be undertaken. The following three brief descriptions are taken from the project countries but serve only to identify occurrences of resettlement. A case of site selection for resettlement of populations in high risk zones in Kigali, Rwanda is, however, provided thereafter below. This case is taken from the recently completed MSc research undertaken by Ms. Alice Nikuze "Towards equitable urban residential resettlement in Kigali", MSc thesis, University of Twente, March 2016.

Some examples of relocation projects in the target countries area:

Belize

Belmopan. Obviously the largest example related to relocation planning in the target countries is the relocation of the capital of Belize from Belize City to Belmopan. After Hurricane Hattie in 1961 destroyed approximately 75% of the houses and business places in low-lying and coastal Belize City, the government proposed to encourage and promote the building of a new capital city.[5] This new capital would be on better terrain, would entail no costly reclamation of land, and would provide for an industrial area. In 1962, a committee chose the site now known as Belmopan, 82 kilometres (51 mi) west of the old capital of Belize City.

Dominica

Saint Sauveur. This small settlement is located along the coast in Eastern Dominica. As can be seen on the left photo a major landslide in Eastern Dominica occurred on 24/05/2010 and killed three people. The government decided to relocate 10 families and with a donation from the Chinese government a resettlement was carried out which was completed in 2015. Unfortunately the relocation site was affected again in August 2015 during tropical storm Erika.

Saint Vincent

A resettlement village for moving people out of the coastal hazard zone was made in a sloping terrain in Manning village on the east coast of Saint Vincent. During Christmas Even 2013 a relatively small landslide occurred on the steep slope above, which killed one of the people in these houses. This illustrates the complicated nature of relocation planning, where there is a very important requirement to find a safe new site.

Gasabo District of Kigali City, Rwanda

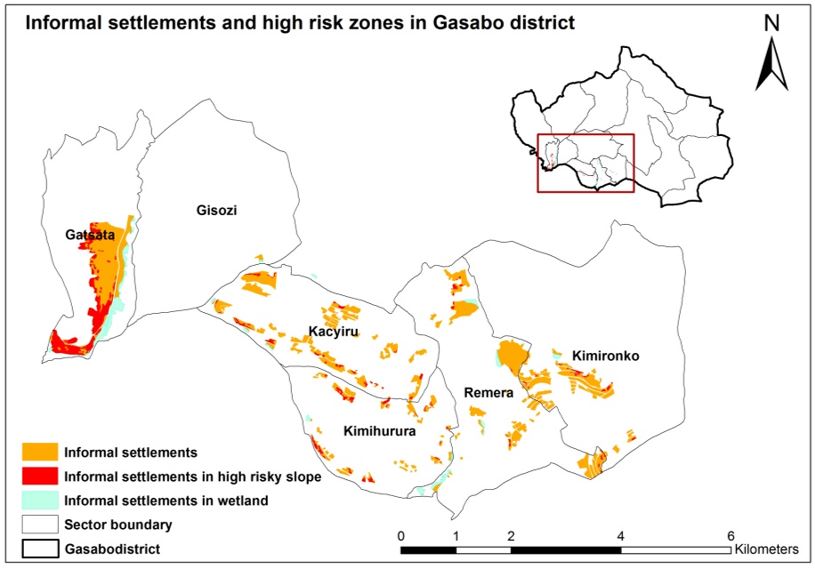

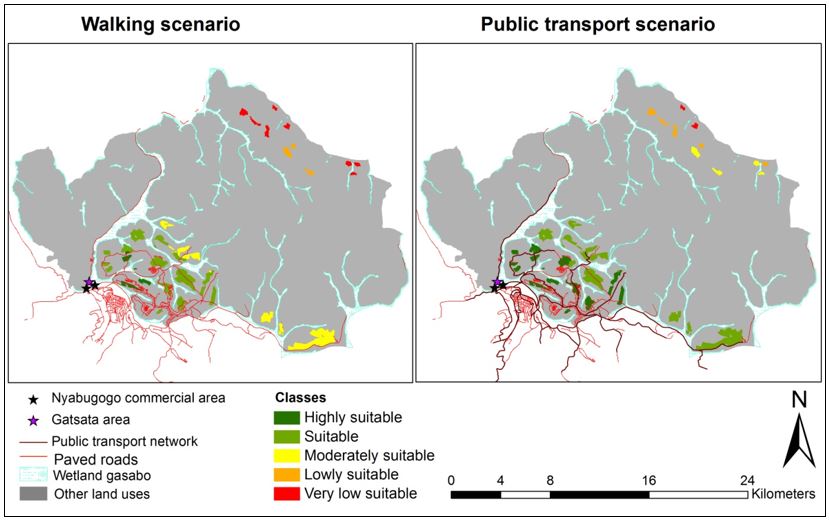

The study was undertaken in Gasabo District of Kigali City where 696 households were found to be located in high risk zones due to excessive terrain slope or flooding. Of these households 455 are located in one area known as Gatsata (see Figure 1 below).

Figure 1: Location of high risk settlements in Gasabo District Kigali.

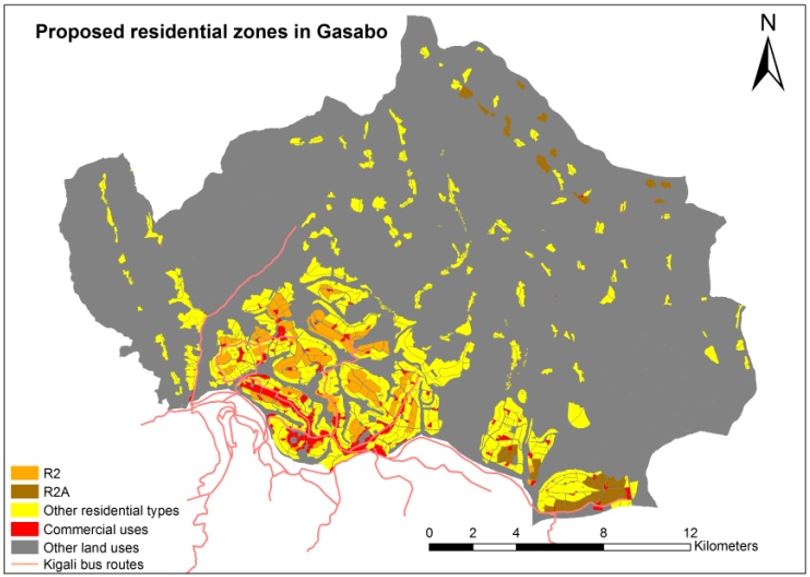

A socio-economic survey was made to understand the characteristics of the affected households: their family composition, assets, and livelihoods were key aspects examined. Kigali Master Plan (Figure 2) has identified various areas for residential use. Zones R2 and R2A are intended for high density residential use and are considered to be most appropriate for the resettlement of low income households. All of these zones are defined in hazard free areas, but they do have different development potentials owing to their locations and other characteristics. It is these characteristics which can be used to rank the potential resettlement sites.

Figure 2: residential zones in Gasabo District Kigali City

On the basis of the household survey and discussions with key stakeholders within relevant ministries and Kigali City several criteria were identified that could be used to evaluate suitable sites for the resettlement of households from high risk locations (Table 1). The effect of steep terrain conditions and variable road surfaces (paved/unpaved) on walking speeds was also considered in preparing the distance maps.

|

Goal |

Criteria |

Indicator |

Impact |

Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Improved livelihood |

Job opportunities

|

Distance to city centre Distance to commercial centres Distance to origin settlement |

Reduce travel time and cost of transport |

Minimum distance, time and cost

|

|

Social facilities

|

Distance to health Distance to education Distance to market |

Reduce long distance and cost of transport |

Minimum distance, time and cost |

|

|

Public transport

|

Distance to bus route Distance to bus stop |

Reduce long distance and cost of transport |

Minimum distance, time and cost |

Table 1: Criteria for resettlement site suitability analysis

These criteria were mapped and weights assigned by means of a step-wise ranking process based upon population needs (Table 2).

|

Rank |

Weight |

Sub-set |

Indicator |

Rank |

Partial Weights |

Overall weights |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1 |

0.667 |

Site location preferences |

Distance to city centre |

1 |

0.5 |

0.33 |

|

Distance to commercial centres |

2 |

0.33 |

0.22 |

|||

|

Distance to origin settlement (Gatsata area) |

3 |

0.167 |

0.11 |

|||

|

2 |

0.33 |

Social public services |

Distance to markets |

1 |

0.33 |

0.11 |

|

Distance to schools |

2 |

0.267 |

0.089 |

|||

|

Primary schools Secondary schools Universities |

1 2 3 |

0.133 0.09 0.044 |

0.045 0.029 0.015 |

|||

|

Distance to health facilities |

3 |

0.2 |

0.067 |

|||

|

Distance to bus route |

4 |

0.133 |

0.044 |

|||

|

Distance to bus stop |

5 |

0.067 |

0.022 |

Table 2: Indicator weights

The final evaluation considered a comparison between two modes of transport (walking and public transport) both of which are frequently used by low income populations. Figure 3 shows the relative suitability of the identified sites. Although some important factors (e.g. land value, land ownership) could not be considered in this study the evaluated sites all have low risk and are consistent with the current Master Plan. A similar approach, adapted to the local circumstances in the Caribbean Island States could form a basis for resettlement site selection and planning.

Figure 3: Overall potential resettlement sites suitability levels

Results:

Throughout the project various outputs will be produced. These range from minutes of Technical Steering committee meetings and quarterly reports for internal and external consumption, to analytical and design oriented products. Of the latter the most important are:

- Detailed hazard and risk analyses of the current site and alternative relocation sites

- Cost-Benefit Analyses of potential mitigation and resettlement alternatives

- Census of PAPs and their assets

- Project monitoring data in the form of indicators and reports

- Database of evaluated resettlement sites (see for example the Kigali City case study)

- Detailed designs for resettlement sites and supplementary guidelines and regulations pertaining to construction on and the use of land.

Conclusions:

The history of resettlement, whether as a result of development or in response to disasters, is fraught with problems. It is an extremely difficult and complex process that can, if badly conceived and implemented, exacerbate poverty and exclusion. The steps described above represent a brief guide to how a resettlement project might be designed and implemented. The use of multiple hazard and risk assessment information is a key aspect of the relocation process: in determining the extent of the area requiring resettlement, in the evaluation of potential relocation sites where it is used to screen potential sites for possible hazards that may affect suitability, and it could also be necessary to consider the effect of a new settlement on existing hazards too. For example, if a new settlement will increase runoff substantially it may generate or increase downstream flooding problems and risks. Such interconnections should be considered when planning large scale resettlement schemes.

References:

One easily accessible source of information on this topic that can serve as a detailed reference document is Correa, E., RamÃrez, F., & Sanahuja, H. (2011). Populations at Risk of Disaster A Resettlement Guide, 157. World Bank GFDRR https://www.gfdrr.org/sites/gfdrr/files/publication/resettlement_guide_150.pdf Also available in Spanish. https://www.gfdrr.org/sites/gfdrr.org/files/BM_Gu%C3%ADa_Reasentamiento_FINALPDF.pdf

Last update: 06-07-2016